“The Institute for the Future couldn’t get clients to read its trend forecasts. So it started giving away prescient product ideas instead.”

“The Institute for the Future couldn’t get clients to read its trend forecasts. So it started giving away prescient product ideas instead.”

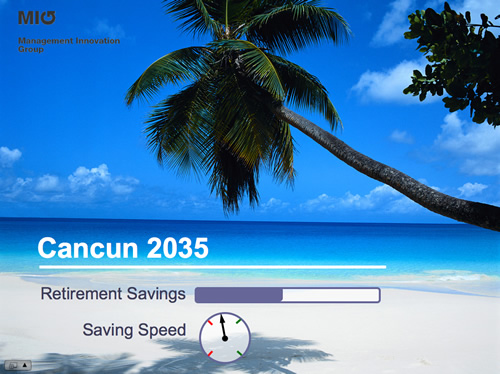

These are great examples of the tangible part of what we’ve been calling Tangible Futures. The IFTF objects seem like good ways to, as they say, ‘start conversations’ about alternate futures. The intention behind our Tangible Futures is a little different. We want to help change the way organizations think about their capabilities and identity so they’re more capable of innovating. The one key difference is that instead of making the artifacts ourselves we think these artifacts are more likely to result in actual innovation if we help companies create their own artifacts. More on this in a moment.

In either case, the conundrum is that we need the tangible artifacts to stimulate the imagination, but then we need to immediately focus away from the artifact to what is required internally for an organization to produce it.

Why? Because innovative companies make innovative products. That sounds obvious, but some companies want to ignore the company part and jump right to the products. To illustrate the difference, consider (surprise) the iPod. Is the difference between the iPod/iTunes ecosystem that Apple had a better idea than everyone else? No. Other companies had already released components of this system, such as hard drive-based mp3 players and online music stores. Sony in particular was the logical one to lead the way, since they possess significantly more portable electronics design, manufacturing, distribution, and retail expertise than Apple. Sony also happens to own a handful of record companies. Apple’s advantage comes down to management innovation. They took smart risks and created effective collaboration across disciplines and groups, where is one place Sony definitely failed. Regardless of which was the better product, the more innovative company won.

Artifacts from the future are highly useful to inspire us into action, but ultimately the challenge is managing people to execute on the innovative ideas. How do we get beyond the focus on the artifact? One approach could be to embed the artifact within a strong story. To use a classic example, we can conjure the story of Adam & Eve using the apple with two bites taken from it. The apple is an artifact that represents a wealth of concepts, and yet our focus is not on the apple, it’s on the people and events.

To develop a corporate vision, scenario planning is a great way for groups to co-create stories about the future. If at the same time the groups create artifacts that conjure those stories, they possess a tangible conveyance, communicating the vision necessary for others to align their work in the same direction. That’s what Tangible Futures is all about.

“The Institute for the Future couldn’t get clients to read its trend forecasts. So it started giving away

“The Institute for the Future couldn’t get clients to read its trend forecasts. So it started giving away