Tangible Futures, Part 1: Background

I’m starting a series of posts to talk about something we’re calling Tangible Futures, which are tangible expressions of visions for the future. That might sound quite ordinary or quite esoteric depending on your point of view, but having worked on it for several months I’m finding it to be a useful practice for the business community in a number of ways.

In this post I’ll try to tie together some important ideas that people have been brave enough to express:

Companies Need a Vision of the Future. John Hagel:

…Ask these same CEOs and their management teams two simple questions:

- What will your relevant markets look like five to ten years from now?

- What will your company need to do in order to thrive in these markets five to ten years from now?

Almost always, the answer will come back that there’s just too much uncertainty to have a clear point of view on this. But, here’s the rub: If the senior management team of a company doesn’t have a clear point of view on where the company is headed, why should investors put a lot of faith in the long-term performance of the company?

Business ideas must go beyond communication and help people change. David Maister:

The real question is: what are the methodologies that really help people change their lives when they understand messages like [Peter] Drucker’s and Tom [Peters]’s? What should they/we be doing differently with our books, our speeches, our videos? Is there a more effective way to actually help people change and make a difference on the world?

Strategic Change Is Useless Without Cultural Change. Tom Peters:

If Drucker and Bennis and Collins and Peters and Co… are/were so damn smart-wise, why is corporate performance so shabby in general?… Strategy don’t matter for diddly if the corporate culture is disfunctional or mis-aligned.

To combine these ideas, we could say that companies need a vision of the future that helps them achieve cultural change. This vision could help executives see future opportunities in a new way. The vision could help executives communicate these opportunities downward (or the reverse could happen, employees communicating opportunities upward).

But this doesn’t often happen now. Some of the problem has to do with the way strategies and forecasts are constructed, which I’ll address in an upcoming post. Some of the problem is simply a fault of the media employed: text and images can communicate ideas, but (at least in a business setting) fail to impart the richness of future situations. And they don’t spark strong emotional reactions that inspire people to care and act differently. We have richer, more interactive media at our disposal: film, theater, environments, computer simulation, and so on. It’s time to start employing them in the service of business strategy.

In the next few posts I’ll show some examples, look at how we can integrate this practice with futures studies, and talk a little about how we can start making tangible futures.

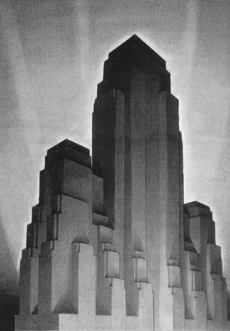

Imagine it is the year 1900 and you own a large corporation needing offices in a major city. You want to construct a building that makes a grand statement of your financial strength and contributes to the civic infrastructure. Currently the highest buildings are about 20 stories, but you are told new construction techniques are capable of building much higher. What would such a structure look and feel like? How much usable office space would there be? Would people want to work that high in the air?

Imagine it is the year 1900 and you own a large corporation needing offices in a major city. You want to construct a building that makes a grand statement of your financial strength and contributes to the civic infrastructure. Currently the highest buildings are about 20 stories, but you are told new construction techniques are capable of building much higher. What would such a structure look and feel like? How much usable office space would there be? Would people want to work that high in the air? My business partner Jim just returned from doing a presentation in Turkey. Notable comment: “Istanbul looks more like San Jose than Constantinople.”

My business partner Jim just returned from doing a presentation in Turkey. Notable comment: “Istanbul looks more like San Jose than Constantinople.”