To solve tough problems, we need the active participation of a diverse group of people. Instead of control residing only with managers, each person on a team should have the authority and responsibility to contribute fully. Rather than command them from above, the team leader should facilitate the team’s efforts.

Since the industrial revolution we’ve needed a lot of science to deal with the changing nature of work. Science in the form of organizational theory helped us structure giant corporations. And the scientific method made time-motion studies possible which vastly increased manufacturing speed. Frederick Winslow Taylor wrote a book in 1911 about the latter field, appropriately titled, The Principles of Scientific Management.

These days our work increasingly consists of complex problems that cannot be divided into simple, repeatable tasks. Take, for example, the Global Earth Observation System of Systems in which 60 countries have agreed to participate in a 10-year effort to collect and share thousands of measurements of the Earth. This data has a wide variety of applications, from monitoring pollution to predicting the weather. But this requires hundreds of scientists with different agendas to agree on thousands of decisions. As one of the project leaders says, “‘We have been able to make computers work together. The challenge of the 21st century is to get people to work together…’ noting that the problem will be overcoming bureaucracy, politics, and turf.â€

Science alone wouldn’t have a chance to make this project work.

The work practices we used throughout the 20th Century are still important and useful. But for complex, 21st Century work they’re not sufficient. Because the problems are bigger, they require more people with more skills to solve them. These complex problems require the combined effort of people with complimentary experience, knowledge, and ways of thinking.

Working involving new combinations of people requires effective collaboration.

Collaboration requires each person on a team to have the opportunity to drive the processes and outcomes.

In other words, success with complex problems depends on sharing control with others. Joe Kraus, the founder of Excite and JotSpot has said, “Very early on, the founders of startups make an important choice. Do they want success or control? …I’ve picked success. And success implies giving up control – hiring people who are much better than you, or being willing to be the janitor if that’s what’s required.â€

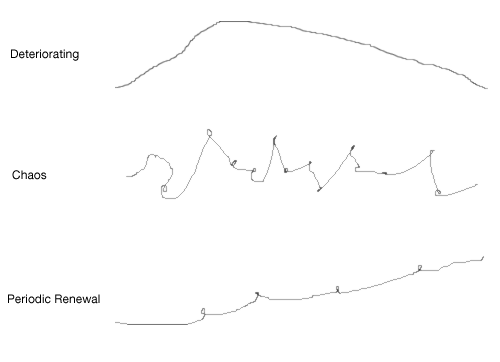

Of course, groups that have no leadership at all can easily slide into a death spiral of debate and fail to accomplish anything. Success today requires balancing control in the form of management with collaboration in the form of facilitation.

Try it now

On an interdisciplinary team, assign a team lead that is a contributing member of the team, but also has responsibility for two critical functions:

- Facilitate the process – This is an art in itself, but it includes eliciting each team member’s best work, resolving conflicts, and finding alternative paths when the team gets stuck.

- Make executive decisions – There will be times when team members will have opposing opinions and can’t resolve them. The team lead synthesizes everyone’s viewpoints, weighs the project priorities, and makes the tough decision, but only when absolutely necessary.