Jess and I thought it would be great to host an event where people could explore the intersection of business, innovation, and design in more depth than conferences allow. So along with some friends we created Overlap which will happen at the end of May. It’s small, non-profit, inexpensive, and centered on conversations. We’re hoping it’s going to be a very special and productive experience. There’s a few places left, if you’re interested in joining us drop me a line.

Category: Business Design

-

Would you come to a business design conference in the U.S.?

Cumulus has planned a conference titled Design Thinking & Innovation: Towards an Asian Perspective in Singapore with Victor Margolin as keynote speaker…

…debating about these topics are a challenge for a symposium aspiring to offer an egression, not a series of positional parametric rhetoric on design issues, but a kind of cynosure to engage, postulate and clarify divergent views on design thinking and innovation, particularly from an Asian perspective.

I think a similar event held in the U.S. — based around discussion rather than presentations — on the topic of business, design, and innovation would be well-received. If it happened, would you go?

-

Numbers can be prototypes

Something I knew on a surface level but didn’t internalize until taking a Financial Modeling class was that numbers can be prototypes.

When financial people build models in a spreadsheet, they’re building prototypes. Just as a designer might sketch on paper or carve a piece of foam, financial modelers will quickly sketch in a spreadsheet (or on the back of a napkin).

What’s odd here is that designers usually think of numbers as representing exact quantities. When a designer writes 100,000 he means 100,000, whereas a financial modeler may mean 100,000 +/-20,000, or she may mean on the order of magnitude of 105 and not 106.

The opposite gap in understanding is true as well. Designers are often hesitant to show clients an early design in the fear the client will misunderstand which aspects are high fidelity and which are low fidelity.

An aptitude for building and understanding different kinds of models seems to be an important skill for integrated thinkers. The question for me is, how can we develop this aptitude, and how to teach it to others? My approaches so far include:

- Gradually move from similar skills you do well to new skills: for example, when learning financial modeling you might start by sketching a graph of the variables, or writing out the financial scenario in prose format, and then turning that into a spreadsheet.

- Play simulation games: which model many different kinds of variables and interactions in a dynamic, interactive way, allowing you to iterate and learn. Making our own simulations will become an important teaching skill.

- Work with someone who already does both well: these are rare, but they do exist.

-

Burning questions

I had an interesting discussion today with a graduate student who is honing in on a thesis question in the intersection of design, innovation, and business. Along the way I remembered I had composed a list of questions that came up during a project last year. These are not necessarily great thesis questions, but they’re certainly things I’d like to know more about, and worth releasing just in case someone is inspired to work on them…

- How can we introduce the uncertainty of wicked problems into organizations accustomed to certainty gained through analysis and hierarchical decision making?

- How does top-down strategic innovation mesh with bottom-up product innovation?

- How can teams seamlessly fuse analysis and creativity?

- Which combinations of skill sets help individuals be innovative?

- How can design theory be applied to business planning and strategy?

- In each of our industries, which skills and techniques are proving successful?

- In each of our situations, which language helps us communicate with colleagues most effectively?

- How does culture determine what kinds of products and services are possible, and vice versa?

- Are there attitudes in our fields that hinder innovation?

- How do organizations accustomed to making decisions based on hierarchy or quantitative analysis alone become more customer-centered and make use of qualitative analysis?

- Can we teach process in a heuristic, modular way that makes it easier for people to use a toolbox of processes as easily as they use a toolbox of techniques?

-

WOW — I DeSIGN

Dr. Charles Burnette’s IDeSiGN — Seven Ways of Design Thinking is the best thing I’ve seen in a while, a curriculum for teaching children how to pursue their goals using different ways of thinking.

Dr. Charles Burnette’s IDeSiGN — Seven Ways of Design Thinking is the best thing I’ve seen in a while, a curriculum for teaching children how to pursue their goals using different ways of thinking.This is designing. It is a process of creative and critical thinking that allows information and ideas to be organized, decisions to be made, situations to be improved, and knowledge to be gained. Purposeful thought and action is the basis for all human achievement and is found in all subject disciplines. Its objective is to change information,understandings or circumstances, to preferred or improved states or to create something entirely new. Because there are many possible outcomes from design thinking it is not easily automated like purposeful thought that has become habitual or has a predetermined result, such as solving a puzzle that has only one solution. Design thinking is a more powerful, comprehensive and creative form of purposeful thinking that can be applied to interpret or resolve complex, confusing, or unanticipated situations whenever and however they occur.

-

Balancing Act: Westin

John Holusha of the New York Times profiles Westin’s decision to move to an all non-smoking format in their hotels. I think this rocks on several levels:

John Holusha of the New York Times profiles Westin’s decision to move to an all non-smoking format in their hotels. I think this rocks on several levels:- It’s progressive, recognizing only 6% of customers request smoking rooms (only half of which actually smoke in the rooms), and this segment isn’t key to their success. Also see Nikon’s move to all-digital cameras.

- It’s good for customers, in that Westin’s in-house smoking cessation program will help the 90% of smoking customers that say they want to stop.

- It’s good for business, creating more flexible room inventory and avoiding the damage caused by smoke and cigarette burns.

It’s a brave thing to aspire to higher goals for your revenue, brand, environment, and customer satisfaction, then design a solution that addresses all of them.

-

Tom and Jerry and management

My colleague Jim, from a recent interview:

My colleague Jim, from a recent interview: I was born in Hollywood and raised in Los Angeles. My father, mother and grandparents all worked in the film industry. My parents actually met when they were both working on Tom and Jerry cartoons. The culture of filmmaking has influenced my approach to design and business. Hollywood offers interesting models for collaboration, ad hoc organization and merging creative and business requirements. Similar practices have migrated to Silicon Valley, and working with clients here was one of the things that sparked my interest in management issues — how we work and the ways in which our working methods influence the products we make.

-

Thinking numerically

I’m taking a class in financial models to round out my skill set. The instructor said something interesting last night, taking care to put us in the right frame of mind for this work. He said, “Teach yourself to see the world in numbers. Try to think numerically.” In that comment I hear that quantitative work is not merely work, it’s a worldview, a mindset. Hearing this, to me, it validates talking about design as a way of thinking, and by investigating different areas I see how they differ but also how they can fit together. As I go through the class I want to see how thoroughly I can mesh the two.

Incidentally, to help one think numerically he recommended the book What The Numbers Say.

-

Employee-Customer mashups

For the sake of innovation, it’s tempting to mash up people internal and external to a company. We’ve seen how important it is that employees be customers, like JetBlue’s employee-centered priorities, and how customers can contribute to companies. This could be one of the most important changes in culture we can bring to companies, but not one of the easiest. Beside the discomfort it will arouse in traditional corporate cultures, we’re still figuring out how to do it.

For example, I’ve realized lately in working to co-create with clients that it needs to be gradual process, because the party you’re creating with doesn’t share the same content or process and needs time to learn. Rather than strive for immediate immersion in creation, I’ve taken a hint from surgeons who say, “watch one, do one, teach one.” Spreading these steps over whole projects may be necessary for both learning and change to happen.

Two more examples come from friends who have recently launched exciting projects that mash up “internal” and “external” resources. Christina Wodtke — a co-founder of MIG — has launched Public Square, software that recognizes the importance of reader-contributed content by allowing quality rankings of people and content to better balance editorial direction and reader input.

And Lou Rosenfeld just launched Rosenfeld Media, a publishing venture in which readers play a vital role in everything from deciding which topics get covered to influencing the actual authoring decisions.

-

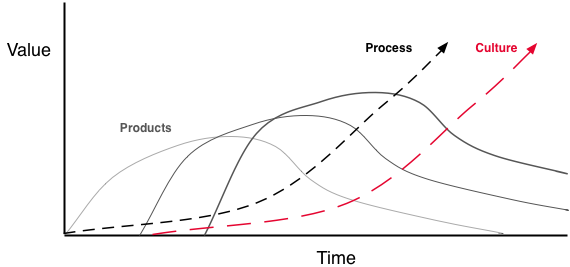

Improvements in products, process, and culture can reinforce each other over time

Improvements in products, process, and culture can reinforce each other over time.

Great products can have a revitilizing effect on a company’s culture. But companies with poor cultures have trouble making great products.

Developing great products relies on an effective process. Cultures that acknowledge the need for process will make better products. But we’re not taught process, so usually we focus on the more tangible products.

Culture can make certain kinds of products and processes possible, but culture is hard to change directly; often it changes through the context of adopting new processes and products.

One approach is to focus on product but introduce process in order for both to change the culture over time.

-

Artful Making

I watched State and Main recently. It’s a movie about making a movie, and hints at how that industry must blend the pure creativity of writing stories, the pure business of running a studio, and the combined creative/business endeavor of bringing together stories and studio to create a movie. I started to wonder if the collaboration and work styles found there was what business designers were trying to create.

I think business design can be much more, yet I think there’s a lot to learn from how people in film and theater run things.

I just discovered a book on this topic, called Artful Making: What Managers Need to Know About How Artists Work…

I just discovered a book on this topic, called Artful Making: What Managers Need to Know About How Artists Work…This book is the result of a multi-year collaboration between Harvard Business School professor Robert Austin and leading theatre director and playwright Lee Devin. Together, they demonstrate striking structural similarities between theatre artistry and production and today’s business projects — and show how collaborative artists have mastered the art of delivering innovation “on cue,” on immovable deadlines and budgets.

One Amazon reviewer compared it to agile programming. Another reviewer noted, “Concepts of rapid iteration, small groups and ‘playing’ …are not new.” Right, and that’s reassuring to me that we keep seeing these concepts applied in productive ways across several disciplines.

-

Designing organic milk

Kim Severson’s article on organic milk production and sales answered a few questions I had, namely

Kim Severson’s article on organic milk production and sales answered a few questions I had, namelyIt’s the low supply, not the production costs, that are keeping the price high. I bet some qualitative research could influence this growth curve. For example, suppose it’s more educated parents who buy organic milk for their kids. Increase organic milk supplies to their geographic areas first and use the profits to increase production elsewhere.

There’s still so much confusion over the “organic” labeling, due to industry/government disagreements. Designers could do an end run and solve this through, for example, smart package design to educate the consumer, e.g.

- Pasture fed

- No artificial growth hormones

- Local cows

- Antibiotics for sick animals

Milk leads organic food sales because emotion plays a large role in this purchase, particularly for parents of babies. Again, this is another area that qualitative research can get the preferred organic products in people’s hands.

-

Mintzberg and Liedtka think it’s time for design

In Mintzberg’s “Strategy Safari” he devotes one chapter to The Design School: Strategy Formation as a Process of Conception. But his description of the cognitive act of design is different from the classic Herbert Simon description. So I appreciated discovering Liedtka’s In Defense of Strategy as Design (pdf), summarized…

This article proposes management reconsider the usefulness of the metaphor of design as a prescription for strategy making, arguing against Henry Mintzberg’s view that it is not appropriate. It reviews literature from the field of design and defines a set of attributes of the design process – which is synthetic, abductive, hypothesis-driven, opportunistic, dialectical, inquiring, and value-driven. The article examines the parallels between designing and creating business strategy and presents the implications of such an approach for designing the processes to design and execute strategy.

(Her Strategy as Design (2MB pdf) is an updated version of this argument.)

Now it seems Mintzberg and Liedtka have joined forces, submitting a piece titled Time for Design, “…making the case for design in management, in four approaches: formulaic, visionary, conversational, and evolving.” I’m looking forward to this one.

-

ID Strategy Symposium and the design-business chasm

Yesterday I attended the Institute of Design Strategy Symposium. The remarks were along the lines of business design we’ve been reading about. What I particularly liked was that the conversation afterwards revolved mostly around the chasm between design and business and the means by which to span the chasm, mostly in terms of language (“design” is a non-starter; “innovation” is more business-friendly but too ambiguous to do anything more than start the conversation).

My colleagues and I don’t buy the stereotype of creative designers vs. logical financial people. There are people with different skillsets and attitudes and the best way to combine them to design new options is through close collaboration (aka co-creation). The example from the Symposium came from Mike Roberts who runs a customer experience group at JP Morgan. He makes progress through direct, personal conversations with people in traditional financial roles. As my friend Bill says, “Collaboration problems are People problems. They are often best solved by increasing the communication bandwidth between people.” The next step, I think, is to work on the best ways to get these skillsets collaborating using modes of conversation, prototyping exercises, boundary objects, and so on.