In my research on concept design processes, I’ve come across two ideas that jumped out as vital behavior that differentiates expert designers from novices.

The first comes from Nigel Cross of Open University, UK, who seems to have studied designers and their processes more than anyone I’ve come across. In his Expertise in Design (pdf) he says (emphasis mine)…

Novice behaviour is usually associated with a ‘depth-first’ approach to problem solving, i.e. sequentially identifying and exploring sub-solutions in depth, whereas the strategies of experts are usually regarded as being predominantly top-down and breadth-first approaches.

While the protocol studies he cites contradict this, when it comes to digital design I find this explains why I see so little concept design these days. Both product developers and designers have a tendency to jump on the first great idea they generate and head down one path, instead of patiently exploring the space of possible solutions. The pain is only felt far down the line when development makes it obvious what doesn’t work and what could have been.

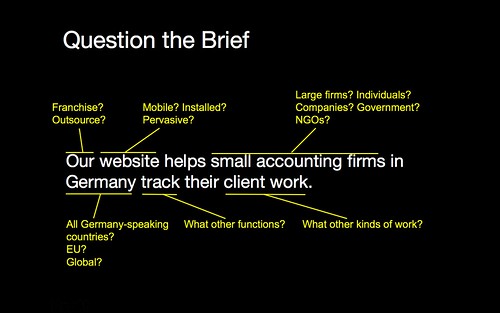

The other big idea comes from How Designers Work, Henrik Gedenryd’s Ph.D dissertation. In the third section (pdf), he observes how designers go about defining the problem to be solved, the most difficult part of the project. How the problem is defined can determine the success of the succeeding design task…

…the two contrasting attitudes make the whole difference between frustration and progress: Quist literally makes his problem solvable, whereas Petra finds herself stuck. The bottom line is that Quist who is the “expert” is acting as a pragmatist, whereas Petra, the “novice”, acts as a realist. And as we have seen, this accounts for a great deal of his superior performance. The choice of either position is not merely a matter of ideology, but has important consequences.

In short, experts are pragmatists, they re-set or re-frame the problem to make it solvable. Novices are realists, they take the problem as a given and get stuck.

We’re pleased as punch to partner with our good friend Lou Rosenfeld at

We’re pleased as punch to partner with our good friend Lou Rosenfeld at