Part of my research into concept design is to look at where successful products and services came from. Today, it’s Twitter.

Lately I’m also perusing Stephen Johnson’s thoughts on Where Do Good Ideas Come From. In this context it’s interesting to read here and here about Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey’s years of experience creating software to dispatch messages, and how this interest goes back to his childhood, so in Johnson’s terminology, the idea for Twitter looks like a slow hunch not a eureka moment, typical of many good ideas in Johnson’s view.

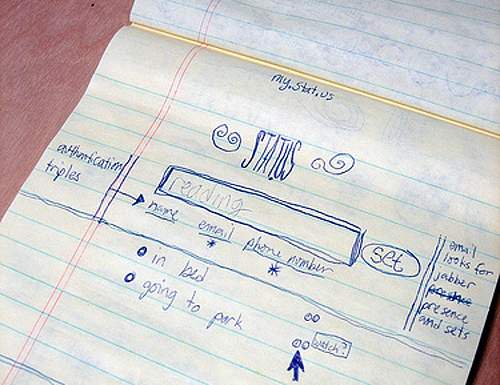

Here’s his sketch from 2000 showing key parts of the user interface:

Fast forward to 2006 via Dom Sagolla:

“Rebooting†or reinventing [Odeo, the struggling podcasting startup] started with a daylong brainstorming session where we broke up into teams to talk about our best ideas. I was lucky enough to be in @Jack’s group, where he first described a service that uses SMS to tell small groups what you are doing. We happened to be on top of the slide on the north end of South Park. It was sunny and brisk. We were eating Mexican food. His idea made us stop eating and start talking.

I remember that @Jack’s first use case was city-related: telling people that the club he’s at is happening. “I want to have a dispatch service that connects us on our phones using text.†His idea was to make it so simple that you don’t even think about what you’re doing, you just type something and send it. Typing something on your phone in those days meant you were probably messing with T9 text input, unless you were sporting a relatively rare smartphone. Even so, everyone in our group got the idea instantly and wanted it.

This telling from an Odeo developer helpfully points out that this session was one of several:

When it became clear that Odeo was not going to become a huge success in the podcasting space, there was a period of soul searching and hack days. One of those hack days, Jack, Noah, and Florian (another rails dev at Odeo), created Twitter. The initial version seemed interesting, Noah, Jack, and Florian kept working on it for several months, while the rest of the team stayed focused on Odeo.

We were limited until 2005-2006 when SMS took off in this country and I could finally send a message from Cingular to Verizon. And that just crystallized — well, now’s the time for this idea. And we started working on it.

and again:

At that time, one of my co-workers introduced me to SMS (short message service), which I had never seen before. She used it all the time. Once I saw that, I’m like, ‘Whoa, this is awesome!’ This communication blew my mind, and the way she was using it blew my mind. I thought, What if we simply set status, archive it on the Web, use SMS to do it, and it all happens in real time? We all kind of went into a corner, wrote out a bunch of user scenarios, and started inviting co-workers in. They fell in love with it. We knew we had something.

A prototype was built in two weeks and Twitter was publicly launched almost four months later.

There’s a few lessons here for anyone creating product or service concepts. One is that slow hunches are slow and take time to evolve. Two, sometimes technology needs to catch up to ideas. Three, nurturing company environments like Odeo help these concepts take shape.

Four, obviously Twitter is a very emergent concept and less goal-oriented than even many startups would attempt; it feels more like a demo you’d see on a Labs page, except it just wouldn’t work on a Labs page. And it’s different than how we usually create concepts that require making money; the New York Times profile states, They freely acknowledged that they had no idea how people would use it or how it would make money. But they thought it had potential…