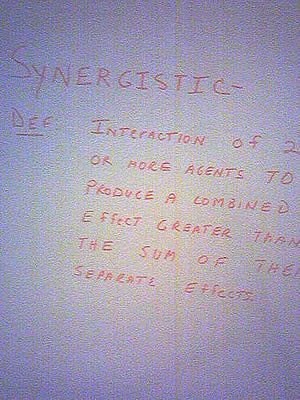

I saw this posterboard in a conference room in corporate America recently:

…and I just had to take a picture of it. While at first it strikes me as a funny word, I’ve been seeing more and more corporate language bashing, and I find it discouraging. It’s too easy to position people who use corporate-speak as the other and label them corporate drones. Language is learned, and so this language acts as useful shorthand to the initiated — which is true in any discipline. If creative and analytical people are going to work together, we need to jump this hurdle.

Synergy is usually the word I think of to illustrate this. It’s hard not to say it without sounding silly because of its use in dot-com exuberance. And yet it has a specific and important meaning to business; the merger of AOL and Time Warner could have resulted in synergy, and that should have been a focus of their integration efforts.

Corporate speak really only fails in two cases:

- When the speaker incorrectly assumes the audience knows the vocabulary, as when government speaks to the public

- When fancy words substitute for substantive ideas. This is really a case of bad thinking and not a language issue.